I listened to the snow bursting under the tires/ like teeth crunching an apple/ and I felt a wild desire to laugh/ at you/ because you call this place hell/ and you flee from here convinced/ that death beyond Sarajevo does not exist

“Corpse” – Semezdin Mehmedinović

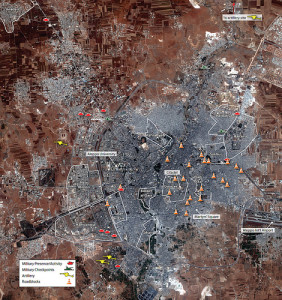

Amnesty International, in cooperation with Science for Human Rights has published a series of satellite images of the city of Aleppo. The images show evidence of the use of heavy weapons and artillery in residential neighborhoods. We knew this, but the independent confirmation is important.

I used to live in Aleppo. The streets and neighborhoods now listed in battle dispatches are places where my friends live, where I shopped for books and went for walks in the evening.

What those satellite images can’t show is the human misery that has befallen the city of some 4 million people. Refugees are moving from one neighborhood of the city to another in advance of government forces and my contacts in the city tell of schools and churches filling with displaced people and shortages of everything. Electricity, water, sewage have failed; food has disappeared from store shelves and state bread bakeries – which feed the city subsidized flat pita – have run out of flour. The specter of kidnapping for profit, which was a hallmark of the civil war in Iraq, is rampant, and the fear of reprisals against Christians and Armenians whose leadership have been among the régime’s supporters grips those communities.

Despite my earlier thought that the Battle for Aleppo would be short, it appears that the Free Syrian Army rebels have dug in. The ferocity of the régime’s response also tells me that for it, recovering the city and dealing a decisive blow to the rebels have become absolute necessities. If it loses Aleppo, it loses northern Syria – from the Turkish border to Iraqi Kurdistan. The rebels would then be able to resupply at will and establish in the city an alternative government. Aleppo would be the new capital of a “Free Syria” – complete with an international airport and the physical infrastructure of a government.

The rebels have fought running battles throughout Aleppo, and have now moved into the city’s ancient walled old city. The old city is a collection of narrow streets, winding alleys and cul-de-sacs. The walls of the houses are made of thick cut stone. The rebels could hold out here for weeks. My fear – beyond the human cost – is that the Syrian army will, as it hunts down its enemies, harm the mosques, churches and caravansaries that led UNESCO to designate the city a “World Heritage Center.”

What the satellite images also confirm is that nothing — international opprobrium, the Geneva Accords, nothing restrains the Syrian army. What I think is happening is that the Syrian Army is beginning to encircle pro-rebel neighborhoods: Salah al-Din, Hannanu, Sakhur, and Ashrafiyya. These are among Aleppo’s newest neighborhoods and are inhabited by immigrants from the countryside. IDPs fleeing fighting near the Turkish border have also fled to these places, often because they have relatives there.

These neighborhoods will then become free-fire zones, where anyone is a target – whether rebel or civilian. This is what the régime did in Homs earlier this year. I’m not sure that this will have any real military value, but act to terrorize the surviving population, and reassure the elite of Aleppo and Damascus that the régime is prepared to do everything it can to stay in power.

Massacres in Aleppo will dwarf what has happened so far.

Aleppo, unlike nearby cities of Beirut, Damascus, or Jerusalem hasn’t been the scene of a battle since the time of Tamerlane some 600 years ago. That doesn’t mean it hasn’t changed hands. Conquerors from the Mamluks, to the Ottomans and the French all preferred to negotiate the city’s surrender to trying to breach its walls and capture its imposing citadel.

I worry that Aleppo will now join Sarajevo in our collective imagination as a once vibrant cosmopolitan city reduced by the fires of hatred to a monument to inhumanity.

I will write more as I am able to resume contact with friends in the city.

A team of UC professors and a leading UC expert on election administration have completed an elections monitoring mission in the troubled region of Nagorno Karabagh. They concluded that the elections adhered to international standards and that this was a critical election in the democratization of the entire Caucasus.

Nagorno Karabagh, an internationally unrecognized republic which broke away from the Republic of Azerbaijan in 1992, held its fifth presidential election this last Thursday (July 19, 2012).

L-R Heghnar Watenpaugh, Karin Mac Donald, and Keith David Watenpaugh at the polling station in the village of Nngi, Nagorno Karabagh

The election returned to office Bako Sahakian with 66% of the vote, and 33% going to his challenger, Vitaly Balasanyan, a former commander in Nagorno Karabagh’s war with Azerbaijan who ran on a platform of anti-corruption and economic development. In a region where past incumbents have often received 80% of the vote, the relative success of challenger Balasanyan is seen as a marked improvement in the democratic nature of that region’s electoral environment.

A team of experts from the UC including Karin Mac Donald of UC Berkeley Law, Professor Keith David Watenpaugh, Director of the UC Davis Human Rights Initiative and Professor Heghnar Zeitlian Watenpaugh, an Art Historian and affiliate of the Human Rights Initiative, were part of a group of Californians that traveled to the troubled region of Nagorno Karabagh to observe its citizens cast ballots.

The team met with elections officials, candidates and their staff, local human rights advocates, including the NK’s Human Rights Defender, journalists and likely voters.

Despite some concerns about voter accessibility and possible voter intimidation, the members of the team observed that the election generally adhered to international standards and was marked by a relatively high voter turnout.

UCB Law’s Karin MacDonald was “very impressed with the professionalism, dedication and training at all levels of election administration, in particular that of local election boards.”

UC Davis Human Rights Initiative’s Keith David Watenpaugh, was equally impressed and while noting his personal concerns about the intimidation of voters, said, “One very important dimension of this election that we observed is that even the major losing candidate and his campaign, despite their allegations of unfairness and irregularities, viewed this election as a critical step in the evolution of a fully democratic society. This same sense of what the election meant was shared by most of the people we spoke with.”

The team’s preliminary report is available at The EARC’s website (EARC.berkeley.edu) and the UC Davis Human Rights Initiative, http://humanrightsinitiative.ucdavis.edu/blog/

Joint UC Berkeley Law, Election Administration Research Center —UC Davis Human Rights Initiative Preliminary Observation Report- Nagorno Karabakh Presidential Election, July 19, 2012

Date of Report: July 22, 2012

Group Composition and Method

The group arrived in Stepanakert, the capital city of the Nagorno Karabakh (NK) on Monday, July 18 and remained in NK throughout the election on July 19, and departed the NK on July 21.

Prior to the election, the group held a series of meetings with NK electoral commission officials, each of the three candidates for office, members of their staff, local human rights advocates, journalists and engaged in random discussions with citizens and likely voters.

On the day of the election, the group used a systematic research methodology based on a comprehensive survey questionnaire designed at the Election Administration Research Center, of the University of California, Berkeley School of Law, completing the survey form based on observing the election at 7 sites, including a pre-election visit to a voting center, and a return visit to one site. These observations included a range of voting centers in the capital, small villages and regional centers. Observations were made in three provinces: Stepanakert, Askeran, and Martuni,.

The observer team was present at a voting center at opening, returning to that same center for closing to observe the ballot counting and reporting procedures.

The team then followed ballots and reporting materials to the Stepanakert regional election center and observed final handling and recording of results and materials. We were the only observer team in NK that followed the entire process.

The day after the election members of the group conducted follow-up interviews with two members of the Central Election Commission (CEC), local human rights advocates, journalists, election observer members from other countries, and representatives of the second place candidate.

Group members:

Karin Mac Donald, Director, The Election Administration Research Center, University of California, Berkeley Law (Election and Monitoring Specialist) Professor Keith David Watenpaugh, Director, Human Rights Initiative, University of California Davis (Cultural Expert, non-native Armenian speaker) Professor Heghnar Zeitlian Watenpaugh, Affiliate Scholar, Human Rights Initiative, University of California, Davis (Cultural Expert, Armenian native-speaker)

Preliminary Observations

The group was very impressed with the professionalism, demeanor, dedication and seriousness of purpose at all levels of election administration, in particular that of local election boards.

We observed large numbers of women voters and that a considerable majority of women served as presidents and members of local election boards.

The teams noted with approval the uniformity of training and availability of reference materials that were widely used on the local level.

We also observed a great deal of uniformity in the implementation of the election process throughout the zone of monitoring.

The team was accompanied, at most times, by representatives of the NK government, who served as translators and facilitators, we appreciated the spirit of openness, access and collaboration before, during and after the election.

We also were satisfied with the manner in which spoiled ballots and ballots that were mismarked were handled according to established procedures as outlined in reference material provided by the CEC. This process was done effectively, transparently and efficiently.

As far as we could observe, the election procedures followed the NK election code.

The group observed that the training and preparation of candidate proxies (“Trusted People”) was inconsistent and seemed generally poor, preventing proxies from being able to fully advocate for the interests of their candidates within the bounds of established procedure.

Despite the presence of voters with physical disabilities, including the use of canes and wheelchairs, there was little if no formal provision made for independent access by people with physical disabilities to voting.

The group observed two occasions of what could constitute attempted voter intimidation. In addition, the team received first-hand reports of subtle and not-so-subtle forms of voter intimidation. The team observed one incident of inappropriate passive electioneering in a polling place.

The leading opposition candidate’s campaign alleged prior to the election in the Armenian press (15 June 2021) that government resources and personnel were being used by the incumbent’s campaign. Subsequent to the election in the candidate’s concession statement (20 July 2012) similar allegations were raised again, as well as in interviews with campaign staff.

We note that interaction between international monitor groups was not facilitated before and after the elections, creating a lost opportunity for collaboration and exchange of expertise. There was no formal mechanism for collecting the observations of international teams.

Preliminary Conclusion

We congratulate the people and election officials of the NK on an election that generally adhered to international standards.

We look forward to analyzing the enormous amount of qualitative and quantitative data we have collected and plan to issue a follow-up report with more specific recommendations. We believe that this election signals the probability that future elections in the NK will be more competitive. This may necessitate a reexamination of ballot security measures.

The degree of voter engagement, high voter turnout, the sophistication and acumen of the electorate, and the civic spirit of the voters suggests that the NK is creating a vibrant and vital democratic society.

One very important dimension of this election that we observed is that even the major losing candidate and his campaign, despite their concerns about fairness and irregularities, viewed this election as a critical step in the evolution of a fully democratic society. This same empowering sense of what the election meant was shared by a broad spectrum of NK society.

We look forward to working with the people of the NK to further strengthen their democratic institutions and provide any assistance that we can as they continue their journey in support of a vibrant, transparent, and free democracy.

Our undergraduates have produced the second number of the 2012 volume of Making the Case.

It is a tremendous effort and represents the work of some of our best and brightest. Several of the authors are Human Rights Minors. Some are going on the Human Rights graduate programs elsewhere. It was edited by Rachel Pevsner, who did a great job.

It’s a mix of historical works, interviews, art and music. I was impressed with all of the work, but especially essays by three of my students:

Geneva Brooks: Barriers to Resistance in Rwanda and the Holocaust

Phoebe Bierly: Genocide Denial and the Stolen Generations

Michael Hoye: Examining the Success of the International Criminal Court

I’ve been away from the Eleanor Blog for some time as I had both a heavy human rights teaching load (Human Rights; Genocide) as well as organizing the Human Rights and the Humanities Week. Which also included a remarkable lecture by the Mideast Director of Human Rights Watch, Sarah Leah Whitson. The week was a great success and the study and teaching of human rights has really begun to blossom at UC Davis, like our redbud and ceanothus plants.

I am coming back to the blog, in part because of real sense of resignation over the turn of events in Syria and in particular the attacks on children. The depravity encompassed by the assault on Syria’s children is a shocking new low, even for the régime in Damascus. 384 have been killed – around 10% of the total casualties and thousands have been rounded up and tortured.

Broadly, it strikes me that this round has to go to House of Assad. The last two weeks’ attack on Hama and Idlib had the feel of “mopping up” operations and weren’t characterized by the slower escalation that took place in Homs. The Syrian régime senses that it can act with impunity and as long as it doesn’t escalate beyond light artillery and tanks, can pretty much do what it wants.

Even though the EC placed additional sanctions on the Syrian super-elite, including Asma, Bashar’s wife, the US has toned-down its rhetoric to delink humanitarian assistance from régime change. This is being done for Russia’s benefit and may lead to some form of real humanitarian help. On the other hand, this public change in rhetoric (the Annan Plan) has given the régime additional space to maneuver.

Human Rights Watch’s reporting on the rebel Free Syrian Army’s (FSA) war crimes, that of the Vatican on ethnic cleansing in Homs and other sources are undermining international support for the FSA and other Syrian rebel forces. Without a reliable non-Assad partner, régime change seems less attractive than “régime reform.” I think that what this also means is that the urban middle-class coalition supporting Assad will continue to do so even though the sanctions will begin to really hurt. For Arab Christians, Armenians and the urban middle-class elite this is an existential problem.

The recent meeting of the Friends of the Syrian People in Istanbul where aid was pledged to the rebels notwithstanding, I don’t see the régime being dislodged anytime soon and rather repression will continue and mount.

However, the international human rights community has begun to call attention to the fact that children are targeted for torture and abuse by the régime to an unprecedented degree. I think it’s worth exploring why the Syrian secret police has adopted this tactic.

First some facts: Human Rights Watch and the UN have both documented widespread detention, torture, and killing of Syrian children.

Human Rights Watch quotes one Hossam, age 13 who was held for three days in a military detention facility in Tel Kalkh:

Every so often they would open our cell door and yell at us and beat us. They said, “You pigs, you want freedom?” They interrogated me by myself. They asked, “Who is your god?” And I said, “Allah.” Then they electrocuted me on my stomach, with a prod. I fell unconscious. When they interrogated me the second time, they beat me and electrocuted me again. The third time they had some pliers, and they pulled out my toenail. They said, “Remember this saying, always keep it in mind: We take both kids and adults, and we kill them both.” I started to cry, and they returned me to the cell.

HRW tells us that Hossam and his family are now refugees in Lebanon.

But what these reports tell us is that the attacks on children are systematic. There is a rhyme and reason to this horror.

This has in large part to do with the role of children in Syrian and Middle Eastern society more generally, as well as the specific position of youth in the Arab uprisings.

We forget this in the West, but children are not just offspring you take care of for 18 years and then they’re out the door. They are your future, especially among the urban lower-middle class and rural people of Syria. They are an investment – a biological 401k. There is little or no safety net and your children will care for and comfort you in your old age.

Children are targeted because of their inherent value to adults. Protecting your children is also a point of honor; taking and torturing them undermines the very stability and integrity of the home.

Reports also indicate that children are being subjected to rape. This is calculated to demoralize and discipline the régime’s opponents, and to suppress the participation in demonstrations and activism by girls, in particular.

Young people – 13, 14, 15 year olds have been at the forefront of the revolutions in the Middle East. Youth has been the vanguard of these movements, in part because of their ability to master social media, and also they know that they have the most to gain from change. I think the Syrian régime also knows that it is involved in a generational struggle for control of the region.

Breaking young people now is a key element of that struggle for the future.

Vaclav Havel was buried today. His state funeral in Prague’s main cathedral was attended by the great and mighty. He would have been uncomfortable with the ritual, but have understood the drama of the moment all the same. Outside thousands of Czechs gathered and their faces showed signs of real grief and sadness at the passing of a playwright who fell into the role of president. He wasn’t the architect of 1989 and the collapse of Soviet power in his homeland, and by most accounts he wasn’t a very good president, as his rigid belief structure wasn’t well matched to the quotidian demands of modern politics.

But what Havel will be most remembered for is how he created an intellectual framework for understanding both the specific content of dissent and the role of the dissident in Eastern Europe as well as a way to see beyond prevailing ideologies of the Soviet Bloc andthe West to something different, something better. His was a rejection of older revolutionary ideologies and models; it was a new understanding through his own lived experience of the transcendent value of dissent and how it is both a product of the dehumanizing nature of modernization and the last best hope for modern society to resist the forces that would finish robbing it of its last shreds of humanity.

His essay, “The Power of the Powerless” (1978) remains the clearest statement of the role of the dissident, his relationship to power, the arts and humanity. Written as a working paper for a meeting of East Bloc human rights defenders that never took place, the essay has the added virtue of telling us something about what is happening today on the streets of Cairo, where tens of thousands occupied Tahrir Square in protest of the violent crackdown on dissent (and in particular on women protestors), demanding the immediate transition to civil rule. It is also a warning about the moral cost of subordinating human life to ideology and “the cause” – a bloody reminder of which we saw today in an upscale Damascene suburb.

At the center of Havel’s essay is the idea that in a totalitarian-bureaucratic state like his 1970s Czechoslovakia or 2010s Egypt and Syria, truth is a product of power: “The principle involved here is that the center of power is identical with the center of truth.” Thus for the “powerless” their power exists in absenting themselves from the truth produced by the state and, in Havel’s words, “living outside the lie.” He uses a “greengrocer” as an everyman around which to explain the process.

Let us now imagine that one day something in our greengrocer snaps and he stops putting up the slogans merely to ingratiate himself. He stops voting in elections he knows are a farce. He begins to say what he really thinks at political meetings. And he even finds the strength in himself to express solidarity with those whom his conscience commands him to support. In this revolt the greengrocer steps out of living within the lie. He rejects the ritual and breaks the rules of the game. He discovers once more his suppressed identity and dignity. He gives his freedom a concrete significance. His revolt is an attempt to live within the truth.

Those of us who have lived in bureaucratic-totalitarian states like Egypt, Syria and pre-war Iraq know this greengrocer and when his brother and sister Cairenes and Homsis took the streets earlier this year, we saw echoes of Havel’s ideas in what they were doing. It was about breaking the power of fear, but also disconnecting truth from the state in ways Havel, whose own ability to share his ideas was limited by the rules of Samizdat, could have only dreamed of. But he understood the cumulative power of that act.

It is a bacteriological weapon, so to speak, utilized when conditions are ripe by a single civilian to disarm an entire division. This power does not participate in any direct struggle for power; rather, it makes its influence felt in the obscure arena of being itself. The hidden movements it gives rise to there, however, can issue forth (when, where, under what circumstances, and to what extent are difficult to predict) in something visible: a real political act or event, a social movement, a sudden explosion of civil unrest, a sharp conflict inside an apparently monolithic power structure, or simply an irrepressible transformation in the social and intellectual climate. And since all genuine problems and matters of critical importance are hidden beneath a thick crust of lies, it is never quite clear when the proverbial last straw will fall, or what that straw will be. This, too, is why the regime prosecutes, almost as a reflex action preventively, even the most modest attempts to live within the truth.

Even as Havel was describing the power of dissent he was looking beyond it to how making the active choice to live outside of the lie and inside of the truth would form a new basis for society.

Above all, any existential revolution should provide hope of a moral reconstitution of society, which means a radical renewal of the relationship of human beings to what I have called the “human order,” which no political order can replace. A new experience of being, a renewed rootedness in the universe, a newly grasped sense of higher responsibility, a newfound inner relationship to other people and to the human community-these factors clearly indicate the direction in which we must go.

Havel located this “moral reconstitution” in the promise of human rights, taking the existence of rights as a serious starting point for morality in a post-revolutionary system. This is the hard (utopian) part of Havel’s thought. He went from being a dissident to being a politician and every dissident loses some of their charm when this happens. It was not an easy transition for him and suggests how difficult such transitions are. But human rights are not at the center of the moral conversation in Cairo. Havel couldn’t have anticipated how Islamist visions for state and society would come to dominate the aspirational idealism of the post-revolutionary environment there, where another kind of truth, dogma is ascendant. For Havel, “life, in its essence, moves toward plurality, diversity, independent self-constitution, and self-organization, in short, toward the fulfillment of its own freedom,” the politics of the moment in Cairo suggest the opposite system and one which in Havel’s words, “demands conformity, uniformity, and discipline” instead.

Yet the bombing in Damascus this morning reminds me that Havel’s theory of the dissident makes it clear that law is at the “innermost structure of the ‘dissident’ attitude. This attitude is and must be fundamentally hostile toward the notion of violent change-simply because it places its faith in violence.” While he does accede to the possibility of violence as a “necessary evil in extreme situations,” he also notes how the dissident is skeptical about any system based on “faith” in change in government or ideological system. What happened in Syria was part of the internationalization of the civil war there and the marginalization of peaceful dissent that advocated for an existential revolution – not just the replacement of one tyranny with another. My thinking is that for Syria, any hope for a peaceful transition is gone.

In the end, the passing of Havel gives us an opportunity to also reflect on the role he believed that art, scholarship and music, especially the raw, malformed rock of the Plastic People of the Universe have, in remaking society.

They may be writers who write as they wish without regard for censorship or official demands and who issue their work-when official publishers refuse to print it-as samizdat. They may be philosophers, historians, sociologists, and all those who practice independent scholarship and, if it is impossible through official or semi-official channels, who also circulate their work in samizdat or who organize private discussions, lectures, and seminars. They may be teachers who privately teach young people things that are kept from them in the state schools; clergymen who either in office or, if they are deprived of their charges, outside it, try to carry on a free religious life; painters, musicians, and singers who practice their work regardless of how it is looked upon by official institutions; everyone who shares this independent culture and helps to spread it; people who, using the means available to them, try to express and defend the actual social interests of workers, to put real meaning back into trade unions or to form independent ones; people who are not afraid to call the attention of officials to cases of injustice and who strive to see that the laws are observed; and the different groups of young people who try to extricate themselves from manipulation and live in their own way, in the spirit of their own hierarchy of values. The list could go on. Very few would think of calling all these people “dissidents.” And yet are not the well-known “dissidents” simply people like them? Are not all these activities in fact what “dissidents” do as well? Do they not produce scholarly work and publish it in samizdat? Do they not write plays and novels and poems? Do they not lecture to students in private “universities”? Do they not struggle against various forms of injustice and attempt to ascertain and express the genuine social interests of various sectors of the population?

The Iraq War ended yesterday. At least it did for the US military. American diplomatic and intelligence personnel and support military contractors are still there in Iraq, and number in the thousands. But America’s war in Iraq has stopped and taking its place is a clumsy and confusing set of policies and programs to try to conserve American interests and influence there after the loss of so many lives and so much money.

As we leave Iraq, we should not forget that it was the site of terrible rights abuses committed by US personnel (Haditha, Abu Ghuraib, FOB Tiger). Iraqis didn’t have to learn how to torture from Americans, they had plenty instruction in that during the rule of Saddam Hussein and his predecessors. But as the torture and rape of Iraqi prisoners in Iraqi detention facilities and black sites has now become routine one wonders how much less bad it could be now had the US been more committed to human rights in the first years of the occupation?

But other question about Iraq’s human rights situation remain – especially as much of the early ex-post facto justification for the war turned on the liberation of the Iraqi people from a truly heinous and barbaric régime, that of Saddam Hussein and the ruling Baath Party. It’s the height of historical revisionism to argue that the war was a human rights intervention, but the US occupation did create space for the emergence of Iraqi civil society, a vibrant and independent media and even governmental structures charged with the protection and promotion of human rights. That said, in the period since 2006 and the Iraqi civil war, the human rights environment in Iraq has deteriorated sharply.

Human rights failures have been the most pronounced in Iraq, as one might expect, in the protection of the country’s most vulnerable: children, widows, as well as marginalized ethnic and religious minorities. And while these groups are often the victims of abuse in other times and places, the central truth of the Iraq War and its aftermath is how it has produced such vast numbers of vulnerable people: 1.3 million refugees, 2 million internally displaced peoples and 500,000 new poor, living in shanty towns without water or proper sanitation. The Red Cross has estimated, for example, that between 1 and 3 million Iraqi households are headed by women, and the numbers of parentless children is similarly large.

But a more systemic problem faces women in Iraq, in that the kind of Iraqi state that has emerged after the war is one that is deeply committed to imposing a religious orthodoxy on society, and in fact wants to reverse any sort of secular gains by women and minorities that occurred in the pre-war period. This has meant not just increasing restrictions of women’s participation in public life, education and commerce. But it has also contributed to violence against women, in particular “honor killing,” a broader social acceptance of domestic abuse and abandonment of prohibitions of child marriage. For Iraqi women the last 8 years have seen their rights in society and even their right to live diminish exponentially.

But perhaps the greatest human rights failure in Iraq is the collapse of state protection for religious minorities. This is both a “security” problem, but also a problem of state will. The case of the Sabian Mandaeans is perhaps the worst. The Mandaeans are an Aramaic-speaking community of monotheists who predate Christianity and Islam in Iraq and live(d) in the major cities, but in particular near Basra in the south. In 2003 there were between 50,000 and 60,000 Mandaeans living in Iraq, now there are perhaps 4,000. Mandaeans have face systematic persecution by religious extremists and have had to flee Iraq. Similar attacks have taken place against Iraq’s Christians and heterodox groups like the Shabaak and Yezidis. Within a generation, most non-Muslims in Iraq will have emigrated, and with them a link to Iraq’s diverse and multi-ethnic past.

A photo from the remarkable work of Jiro Ose “Living in the Shadows: Iraqi Refugees”

As Iraqi politics begins to resemble less democracy and more a rehabilitated Arab authoritarianism, as press freedom evaporates and conservative Shiite political Islam dictates social and cultural norms, the nascent human rights régime in Iraq will be strangled.

Perhaps the only thing we have left to give the Iraqi people is integrating clearly concerns about Human Rights into the new bilateral “partnership” between the US and Iraq.